Sign Up For Our Newsletter

Thank you for signing up!

Something went wrong! Please try again.

© 2026 AnChain.AI. All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy

The arrest of Tornado Cash developer Roman Storm in 2023 wasn’t just another crypto headline, it marked a turning point for privacy on the blockchain. For the first time, a decentralized smart contract became the center of a criminal prosecution, sending shockwaves through the entire industry. The message from regulators was clear: privacy tools can no longer hide behind decentralization or plausible deniability.

At the same time, the tension between transparency and privacy has never been sharper. Blockchains make every transaction public forever, exposing salaries, donations, and personal spending to anyone with a block explorer. Yet tools that restore financial privacy can also shield cybercriminals, sanctions evaders, and fraudsters. The future of programmable privacy now hinges on one urgent question: can we build systems that protect honest users without giving bad actors cover? This blog kicks off a series examining how crypto privacy protocols are evolving to answer that question.

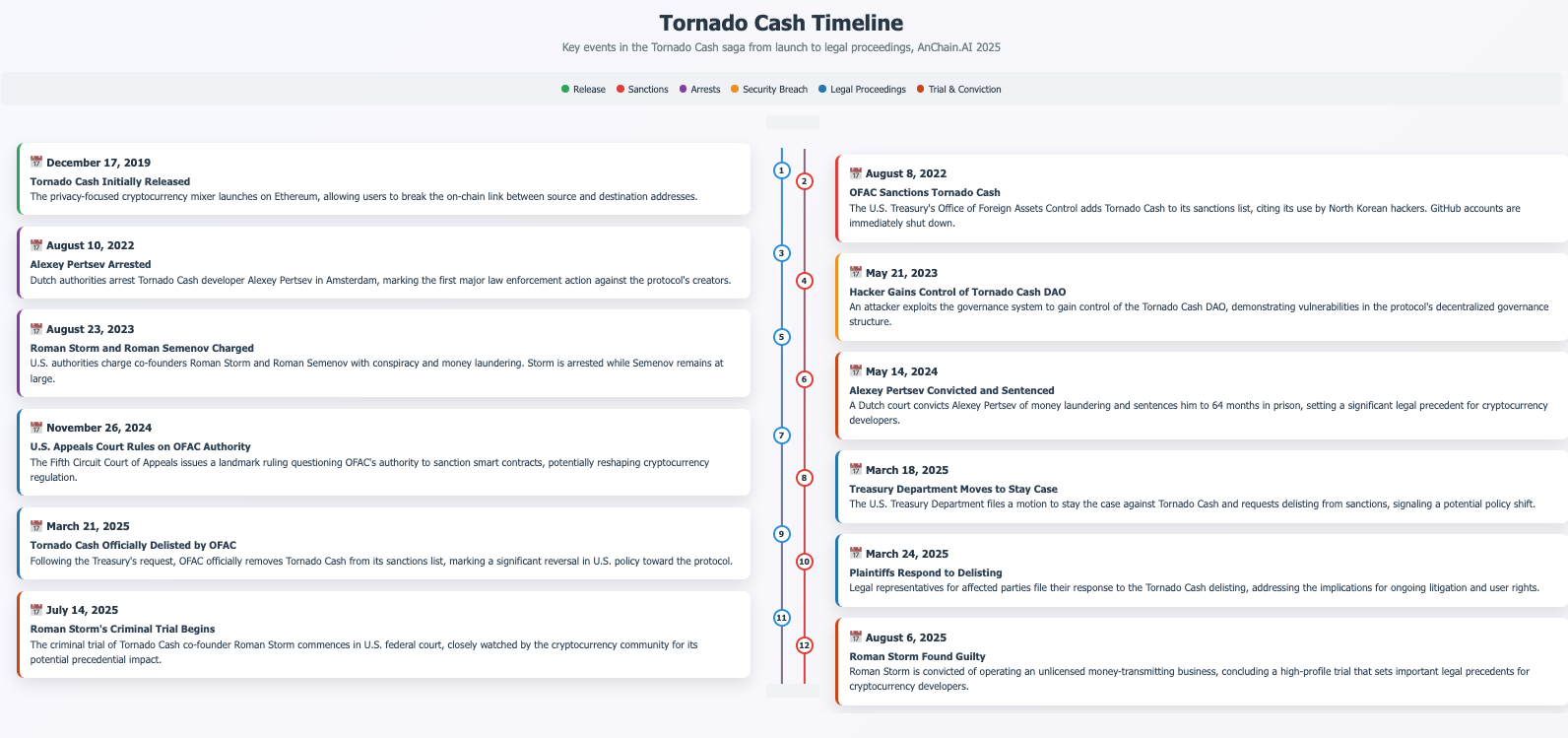

Tornado Cash timeline of events

Governments have long recognized the dual-edged nature of private systems. When banks began facilitating large-scale money movements, they were eventually brought under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) in 1970. This legislation laid the foundation for mandatory recordkeeping, customer due diligence, and the now-familiar Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs). Over time, with support from international bodies like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), these compliance obligations expanded to cover almost every corner of traditional finance.

The 9/11 attacks catalyzed the USA PATRIOT Act, which gave law enforcement broader authority to track financial flows linked to terrorism. Banks, willingly or not, became deputized nodes in the surveillance infrastructure of the modern financial system.

A parallel unfolded in telecommunications. The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994 required telecoms to build systems that enabled lawful wiretaps. Later, the push for backdoors in encrypted messaging apps like Signal and iMessage triggered debates over whether privacy should ever trump law enforcement needs. While many of these companies resisted backdoors, they still have legal entities and can be compelled to cooperate with subpoenas and warrants. The core lesson? When a private system becomes critical infrastructure, whether for money or communication, governments will demand visibility and accountability. This brings us to Tornado Cash.

Tornado Cash was a privacy protocol deployed on Ethereum that allowed users to break the link between deposit and withdrawal addresses using zero-knowledge proofs. Users would send ETH or ERC-20 tokens to Tornado’s smart contracts, wait for a delay, and then withdraw to a new address effectively achieving on-chain anonymity.

It was an elegant technical solution to the blockchain transparency problem. But its power came with risk. By design, Tornado Cash had no mechanism to distinguish between honest users and bad actors. It couldn’t block sanctioned entities, and it couldn’t retroactively exclude criminal funds. This neutrality, a core ethos in decentralized systems, proved to be its undoing.

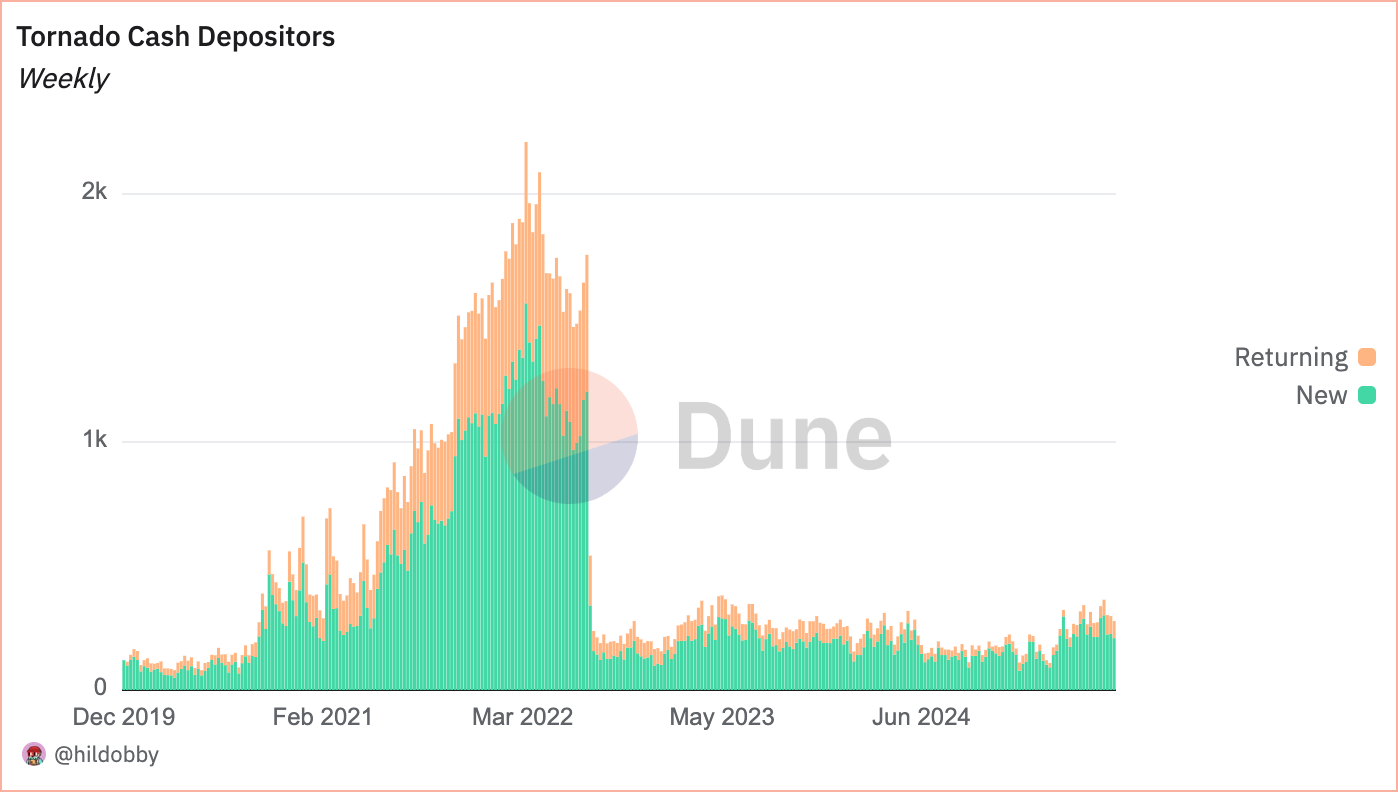

In August 2022, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Tornado Cash, citing its use in laundering over $1 billion in illicit funds, including by North Korea’s Lazarus Group. The designation made it illegal for U.S. persons to interact with the protocol’s contracts. The fallout was swift: GitHub accounts were shut down, the community fractured, and two of its developers, Alexey Pertsev and Roman Storm, faced arrest and prosecution.

Tornado Cash became the first decentralized smart contract to be sanctioned by a major government. It set off alarm bells across the privacy ecosystem: clearly, plausible deniability and decentralization would no longer be enough.

Tornado Cash withdrawal transaction visualized in AnChain.AI SCREEN Platform (link)

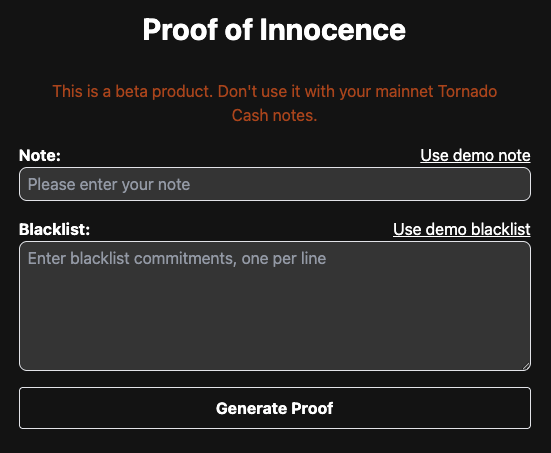

Before the sanctions, Tornado Cash included a rudimentary but important feature intended to support user-side compliance: the Tornado Cash Compliance Tool. This tool allowed users to generate cryptographic proof that a specific withdrawal was linked to a known deposit. The idea was simple: a user could voluntarily reveal a deposit note to prove ownership of funds that had been withdrawn, without disclosing their identity on-chain.

The compliance tool generated a Merkle proof and zero-knowledge SNARK showing that a withdrawal stemmed from a specific deposit, allowing users to demonstrate the legitimacy of their funds to exchanges, auditors, or regulators. For example, if an exchange flagged a deposit as suspicious because it came from Tornado Cash, the user could provide a compliance report showing they had deposited their own ETH into the pool days earlier and were simply withdrawing it.

But like many early privacy designs, this feature was opt-in and user-controlled. There was no way to force bad actors to use it or prevent them from abusing the system. Tornado Cash itself remained agnostic to user behavior: the smart contracts were immutable, permissionless, and lacked any enforcement mechanism.

Ultimately, this limited compliance gesture was not enough. Regulators viewed it as insufficient—a voluntary proof system in a protocol being actively used by sanctioned entities. It highlighted a key theme in privacy protocol development: compliance features must be mandatory, enforceable, or externally verifiable to earn trust from regulators.

Tornado Cash compliance tool UI

In the months following the Tornado Cash sanctions, the community began experimenting with ways to prove a withdrawal was legitimate without sacrificing privacy. The most notable development was the creation of Proof of Innocence (PoI).

Specifically, Chainway’s PoI for Tornado Cash enabled users to generate a zero-knowledge proof demonstrating their withdrawal does not originate from any deposit flagged as illicit based on a blacklist of known bad notes. It’s a ZK exclusion proof: users prove non-association with bad actors while preserving full anonymity.

This system was later adopted by Railgun, generating zk-SNARK proofs at deposit time to assert that funds are clean with respect to a list of suspicious addresses. This proof travels with the funds, so exchanges or counterparties can verify withdrawals independently. For a deep dive into Railgun’s PoI see our blog Why Did Railgun’s Proof of Innocence Fail?, or wait for the next blog in this series.

But here’s the core issue: Tornado Cash’s PoI remained an optional, user-controlled measure, and it did not change its legal status. U.S. entities remained prohibited from interacting with the protocol, even with a verified PoI. So while it planted an important seed, that privacy and compliance can coexist, it fell far short of satisfying regulators.

Chainway Proof of Innocence PoC UI

Since the initial sanctions, there have been important legal and regulatory developments.

In 2023, a U.S. federal court ruled that sanctioning the immutable Tornado Cash smart contracts themselves may have overstepped OFAC's authority, raising questions about the constitutionality of blacklisting code rather than entities. This ruling suggested that open-source code and decentralized protocols may not be subject to the same treatment as traditional financial intermediaries.

Meanwhile, Roman Storm was found guilty of operating an unlicensed money-transmitting business, and Alexey Pertsev was convicted in the Netherlands and sentenced to over five years in prison. These cases hinge on complex questions about developer liability, intent, and control over decentralized protocols. At the heart of the legal debate is whether protocol creators can be held accountable for the actions of users on systems they no longer control.

While the GitHub accounts and repositories associated with Tornado Cash were initially removed, GitHub later reinstated them in read-only mode following criticism from civil liberties organizations.

These evolving legal interpretations underscore the uncertainty developers face when building privacy tools, and they highlight the urgent need for protocols that can demonstrate both privacy and compliance.

Tornado Cash deposits over time (https://dune.com/hildobby/tornado-cash)

Tornado Cash may have been the first to fall, but it won’t be the last protocol tested by regulators. What comes next is a new wave of privacy systems designed with compliance-by-design: mechanisms like association sets, on-chain risk scoring, and selective de-anonymization.

In the next blog, we’ll explore how protocols like Privacy Pools, Railgun, Labyrinth, and more are building these features from the ground up, not as an afterthought, but as a core part of how privacy should work in a world that demands accountability.